Far from a commonly held view, the sea is not a legal void where the responsibility of States and individual actors is inexistent. It is an area that has been governed by international law for centuries. The rights and obligations of States do extend into the sea through different maritime jurisdictions and several fundamental rights apply to migrants attempting to cross the sea, regardless of their nationality or legal status. This section offers a brief introduction into this complex and technical issue.

Maritime jurisdictions

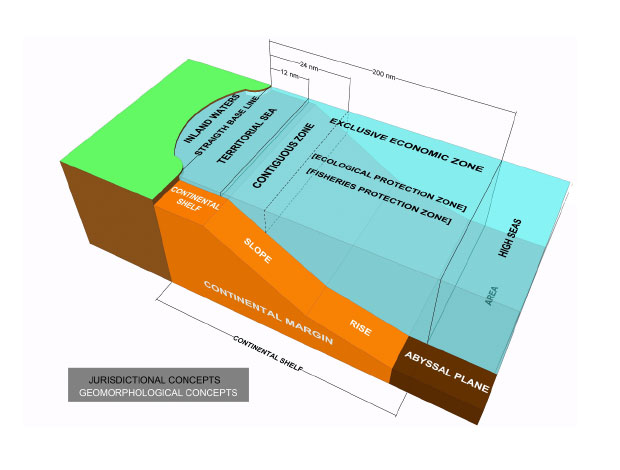

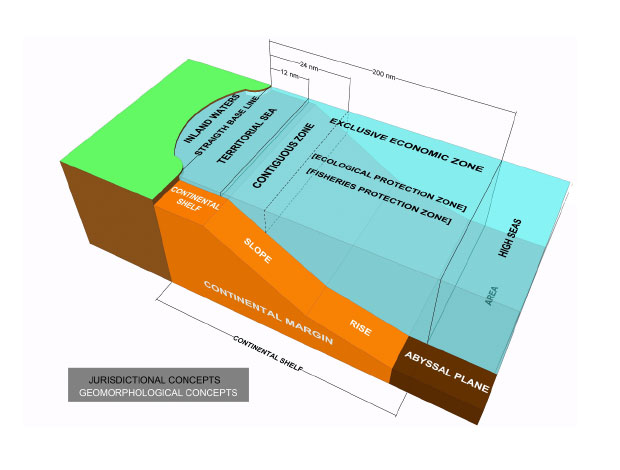

The oceans cannot be occupied as can a piece of land and no state has ever had the capacity to exercise full sovereignty over them. Throughout history states have however sought to exercise control over navigation and maritime resources all the while enabling a degree of freedom of navigation. The current structure of the maritime territory and the codification of states' rights and responsibilities at sea is mainly established by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Maritime jurisdictions today resemble an “unbundled” sovereignty, in which the state’s rights and obligations that compose modern state sovereignty on the land are decoupled from each other and applied to varying degrees depending on the spatial extend and the specific issue adressed.

Juan Luis Suárez de Vivero, Jurisdictional Waters in The Mediterranean and Black Seas, European Parliament, 2010, p. 27.

Article 8 of the UNCLOS provides that a state's full sovereignty and jurisdiction extend into its inland waters which form a part of the country’s territory. States also have full sovereignty within their territorial waters, which may extend up to 12 nautical miles from the base line (UNCLOS, Arts. 2, 3 and 4). The state may further exercise certain police functions (take customs, fiscal, immigration or health measures) within its contiguous zone, that may not exceed 24 nautical miles from the baselines (UNCLOS, Art.33). Finally the coastal State has exclusive powers of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources within an Exclusive economic zone of a maximum of 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the territorial sea is measured (UNCLOS, Arts. 55, 56 and 57). Beyond these zones, the maritime area is called “high seas” and no State can exercise its full sovereignty and purport to subject any part of the high seas to its jurisdiction. The high seas are free for all States and reserved for peaceful purposes (UNCLOS, Art. 88). However, the high seas do not become as a result a “legal vacuum” since the rights and obligations of each actor and states are framed by international law. The jurisdiction of states applies to boats flying their respective flag, and each boat thus becomes a small piece of “floating state jurisdiction”.

Migrants’ rights at sea

The main rights and obligations concerning migrants attempting to cross the sea clandestinely are framed by the following legal norms:

The right to leave any country, including his own and its limits

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that:

"Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country” (Article 13. (2)). Article 5 of the 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination provides that state parties undertake to prohibit and to eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms and to guarantee the right of everyone, without distinction as to race, colour, or national or ethnic origin, to equality before the law, notably in the enjoyment of [c, ii)] the right to leave any country, including one’s own, and to return to one’s country."

Article 12 of the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights reaffirmed this right but with limitations:

2. Everyone shall be free to leave any country, including his own.

3. The above-mentioned right[s] shall not be subject to any restrictions except those which are provided by law, are necessary to protect national security, public order (ordre public), public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others, and are consistent with the other rights recognized in the present Covenant.

4. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter his own country.

It is thus difficult to say what is the exact rule in international law defining the right to leave any country, including ones own. Nevertheless we can observe that several Non-EU States on the Southern shores of the Mediterranean punish undocumented exit from their territory (for example Tunisia and Algeria) and criminalise assistance to this practice.[1] Furthermore, neither the Universal declaration nor international customary law establish a right to enter another State, and as such the right to exit remains paradoxical and incomplete. Immigration States maintain restrictions on entry and have the right to “intercept”[2] migrants at sea within the limits of their territorial waters or contiguous zone to prevent them from entering without mandatory documents. Furthermore, in exceptional circumstances, a “right to visit” may be exercised by a State on a foreign vessel. In particular, the supposed lack of flag of boats used by migrants crossing the sea clandestinely is the main basis allowing states to exercise interception in the high seas.[3]

However, while States thus have the right to exercise control over navigation and to intercept migrants in certain circumstances, they also have obligations to treat migrants at sea according to international law, in particular concerning rescue at sea and asylum.

The obligation to rescue people in distress

Rescue of people in distress at sea, regardless of their nationality or status, is an unconditional obligation for all ships in vicinity and coastal state authorities. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS Convention) provides that:

“ Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag, in so far as he can do so without serious danger to the ship, the crew or the passengers: (a) to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost; (b) to proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distress, if informed of their need of assistance, in so far as such action may reasonably be expected of him.” (Art. 98 (1))

Furthermore, the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea imposes an obligation on every coastal State Party to:

“...promote the establishment, operation and maintenance of an adequate and effective search and rescue service regarding safety on and over the sea and, where circumstances so require, by way of mutual regional arrangements, co-operate with neighbouring States for this purpose”. (Art. 98 (2))

The Guidelines on the Treatment of Persons Rescued at Sea (adopted in May 2004 by the Maritime Safety Committee together with the SAR and SOLAS amendments) contain the following provisions:

“The government responsible for the SAR region in which survivors were recovered is responsible for providing a place of safety or ensuring that such a place of safety is provided.” (Resolution MSC.167(78), para. 2.5).

Despite these obligations, the politicisation of the disembarking of migrants following rescue (see

The Sea as Frontier) has led states to be increasingly reluctant to enforce their obligations to operate rescues. Some states such as Tunisia and Libya have not defined their SAR zones. Other states such as Italy and Malta have overlapping SAR zones and are signatories to different versions of the SAR convention. This leads to constant diplomatic rows as to which state is responsible to operate rescues or disembark migrants who have been rescued by seafarers. In some instances assistance has been criminalised, with those lending assistance to migrants in distress being accused of “assistance to illegal migration”. Combined, these practices have led to repeated failures in the unconditional obligation to assist people in distress at sea.

The Right to Seek Asylum

If people rescued at sea make known a claim for asylum, key principles as defined in international refugee law need to be upheld.

The 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, defines a refugee as a person who: “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his [or her] nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself [or herself ] of the protection of that country”. (Article 1A(2))

It further prohibits that refugees or asylum-seekers “… be expelled or returned in any way “to the frontiers of territories where his [or her] life or freedom would be threatened on account of his [or her] race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” (Article 33 (1)).

The scope of the principle of non-refoulement has a larger scope in the field of Human Rights Law. Indeed, it protects every person and not only the refugees and asylum seeker and the scope of its protection is larger. Human Rights prohibits every expulsion or refoulement to a country where the person is at risk of suffering torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, sometimes the execution of the death penalty and sometimes a grave denial of justice [4].

Despite these obligations, of which the applicability to the high seas has recently been reaffirmed by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in the judgement on the Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy case, State agencies have repeatedly operated “push-backs” – deporting intercepted migrants to countries in which their life could be in danger without allowing them file a claim for asylum.

For more information:

Juan Luis Suárez de Vivero, Jurisdictional Waters in The Mediterranean and Black Seas, European Parliament, 2010

Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen and Tanja E.Aalberts, Sovereignty at Sea: The law and politics of saving lives in the Mare Liberum, DIIS Working Paper 2010:18,

Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly Doc. 12628, Committee on Migration, Refugees and Population, Rapporteur: Mr Arcadio Diaz Tejera, The interception and rescue at sea of asylum seekers, refugees and irregular migrants, June 2011.

Footnotes